I am autistic. One of the ways I try to contribute to the communal well being of autistic people is to participate in research studies. I recognize that my participation comes from a place of privilege in that I have the capacity and financial and time security to be able to afford to do this work, and I do my best to present an honest take on what the autistic experience is like while simultaneously trying my best not to speak over other autistics or claim to speak for everyone.

One of the ways that I contribute to these surveys is by helping with usability testing before they’re put to use collecting data. Being autistic for me can express itself as being very picky about details. I don’t have formal training in survey design, nor do I have enough statistics knowledge to help crunch the results, but I am autistic and I’ve taken enough of these assessments to have a good idea of what makes a good or bad one.

Recently, I was asked to participate in a study about the way autistics produce and receive non-verbal communications like facial expressions and body language. This is something I struggle with a lot personally, and is one of the reasons I argue that the RUSA behavioral guidelines are ableist. Unfortunately I was asked to assist as a study participant, rather than an accessibility pre-screener, so by the time I saw this trainwreck of a question it was too late to salvage:

How often does the following barrier make it hard for you to communicate? Remember to focus on times when you are comfortable and things are going your way.

“People think I am communicating nonverbally when I’m not actually trying to communicate anything nonverbally.”

- When I use a matter-of-face tone, people think I am being rude.

- When I move my eyebrows as a stim, people think I am angry.

- When I fidget to help myself pay attention, people think I am bored.

- When I don’t make eye contact, people think I am lying.

- None of the time

- Some of the time

- About half of the time

- Most of the time

- All of the time

First let’s take a look at the pre-question instructions. I’m supposed to focus on times when things are going my way. But I’m faced with a communication barrier, which means things aren’t going my way. Right from the start, I am receiving conflicting instructions.

The main text of the question is relatively straightforward, which I appreciate! It asks exactly one question. And if that’s all there was before we got to the answer scale, that would be fine. But sadly, they don’t stop there. I think the intention with the following list was to provide examples of situations where people mistake behavior as non-verbal communication, but what’s actually communicated is four different situations. What if I don’t use a matter-of-fact tone? What does that term mean? How would I know if people think I’m being rude or not? Or if they think I’m angry, or bored, or lying? What if I do make eye contact, or don’t fidget, or never move my eyebrows?

Not only are we no longer dealing with a single question but a dozen, each one is problematic. Autistic people often (but not always) struggle with understanding what other people are thinking or feeling, but in order to answer the question I have to be able to accurately assess someone else’s emotional perception. We often (but not always) have trouble regulating the volume and pitch of our voice and may not notice when others don’t consider our tone to be “matter of fact.” Some autistics, but not all, have difficulty making eye contact, and including this is arguably playing to a stereotype.

When I got to the answers, I was too mixed up to begin to assess what percentage of the time I was correctly guessing how others perceived my behavior. But that wasn’t even what the question was about. On top of figuring all of that out, now I also have to assess how often that perception of my behavior was a communication barrier.

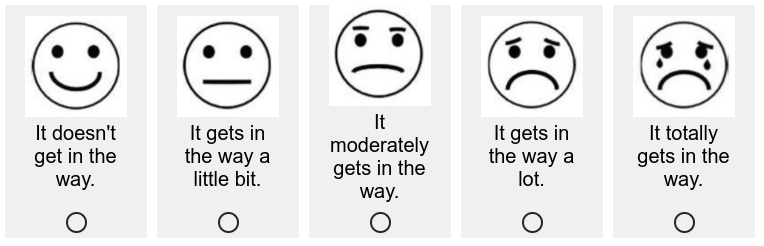

And each question is two parts. After the first “how often” part, they ask the same question with “how big of a problem” is the communication barrier for me. The options range from “It doesn’t get in the way” to “it moderately gets in the way” to “it totally gets in the way.” And if that’s all they were asking, it wouldn’t be any worse than the first part of the question. But in addition to these text descriptions asking me to assess how significant the impact of the communication problem is, each text point was accompanied by a visual representation of an emotional state called a Wong–Baker Scale:

The Wong-Baker scale is intended to help assess pain, or in this case the emotional impact of the communication barrier. So it’s not just an objective emotion-free assessment of the communication impact, but now I’m asked to also assess how that impact makes me feel. Did you know that autistics often experience alexithymia, a condition that makes it difficult to identify emotions? And we’re back to the asking more than one question issue. Even if you get past the problematic text of the question itself, every answer here is asking me to evaluate two different things. If it gets in the way of communication but doesn’t make me upset, do I pick the left or right end of this scale for my answer? And that’s not even mentioning the trauma many autistic kids experienced at the hands of ABA “teachers” who would deny us access to restrooms until we correctly identified emotions supposedly being communicated in photographs of faces.

Survey design is not an easy task to get right. It’s especially difficult when you’re attempting to assess a group that has cognitive and emotional differences from the person designing the assessment. It is critically important that designers get feedback from people trained in survey design and from the population it’s intended to assess.

This is not the worst survey I’ve seen, but it has significant flaws. I chose not to participate in this study because I do not believe any valid conclusion could be drawn from the responses to questions this poor. When you’re looking at the results of research like this, especially when it’s ostensibly meant to represent the capacity or state of a marginalized community, be sure to evaluate the study questions and not just the results. This post has examined a single question from a single survey, and while I feel it’s a good example of the problems I see in many of these studies, sometimes there are good studies that don’t have these problems.

If you’re designing a study like this, feel free to contact me and I’ll give my feedback on it if I have time.